Netflix’s 'Ripley'... mesmerising or charmless

News publisher Out claimed Scott’s Ripley for gayness. However, Scott’s own aspirations are more ambiguous, saying “he’s a queer character, in the sense that he’s very ‘other’.”

In the novel, Tom Ripley is sent to Europe by Dickie Greenleaf’s father to persuade him to come home to America. However, once he arrives, Tom becomes obsessed with Dickie and his lifestyle. When Dickie rejects him, he kills him and steals his identity. And this is only the first of his murders.

Highsmith wrote Ripley as having an elusive sexuality. As the character Marge says in the book, “He may not be queer. He’s just a nothing, which is worse. He isn’t normal enough to have any kind of sex life.”

Each era since Highsmith’s novel has had its own screen version of Ripley, responding to its own sexual and moral times. Scott’s Ripley is different yet again: an enigma who is both compelling and frightening – connected to sexuality, but resistant to explanations, labels or pigeonholes.

Tom Ripley through the ages

Previous adaptors have “solved” the problem of Ripley’s ambiguous sexuality and amorality by pigeonholing him, and making sure he got caught — both of which Highsmith pointedly avoided.

In 1960, director René Clément made Ripley straight in Plein Soleil. In the final scene, the police close in to arrest him. In 1999, Anthony Minghella made him gay in The Talented Mr. Ripley.

Minghella asserted that Ripley’s “pathology is not explained by his sexuality”, yet he punishes Ripley through his gayness when he has him kill his lover.

Refreshingly, Claude Chabrol’s Les Biches, thought to be loosely based on The Talented Mr. Ripley, neither pigeonholes nor punishes its lesbian/bisexual protagonist. The film was made against the countercultural foment of 1968. Its protagonist is so anonymous she is known only as “Why” and is not caught.

Scott’s Ripley is equally sensitive to its times. Scott said he and director Steven Zaillian were “very concerned with labelling in 2024. […] Ripley wouldn’t be comfortable in a gay bar; […] he wouldn’t be comfortable in a straight bar.”

Embracing gayness and fluidity

Gayness as a whole is not subtext in Zaillian’s production. Freddie Miles (Eliot Sumner) is explicitly gay. Dickie Greenleaf (Johnny Flynn) asserts “I’m not queer” in the defensive manner of “someone who absolutely is”, as observed by Digital Spy’s David Opie. Ripley plants a kiss on Freddie’s corpse while manhandling it. Inspector Ravini (Maurizio Lombardi) suspects Dickie and Miles were “involved”. And, finally, Ripley projects his own gay crush back onto Dickie.

At the same time, the series shows a sincere commitment to fluidity. Non-binary Sumner plays Freddie Miles, their slight embodiment contrasting with Philip Seymour Hoffman’s fleshy, aggressive, bitchy, camp machismo in Minghella’s adaptation.

The choice to embrace fluidity is also strategic as it keeps Zaillian open to sequels that could stick to Highsmith’s original plots. In subsequent Ripliad novels, Tom marries a woman. Although there are ongoing hints of bisexuality, Highsmith said, “I don’t think Ripley is gay. […] I’m not saying he’s very strong in the sex department. But he makes it in bed with his wife.”

If this is confusing, it is because Highsmith herself was a contradictory figure. She was a lesbian, but exhibited internalised homophobia. She was a woman, but wrote a collection of stories entitled Little Tales of Misogyny.

Her Ripley oscillates between the identities Dickie and Tom in The Talented Mr. Ripley, and between points of sexual identification in the wider Ripliad in an uneasy way that destabilises fixed identities. Ripley is by turns gay and straight, queer and nothing.

Scott plays an incalculable Ripley

So, does Scott do well at playing “nothing”? On one hand, the actor has said, “sometimes the reason we feel unnerved by certain people is because we don’t know their backstory […] What’s wonderful about Ripley is we have no idea.” But he has also said “it’s actually the blankness that’s sometimes hard to engage with”.

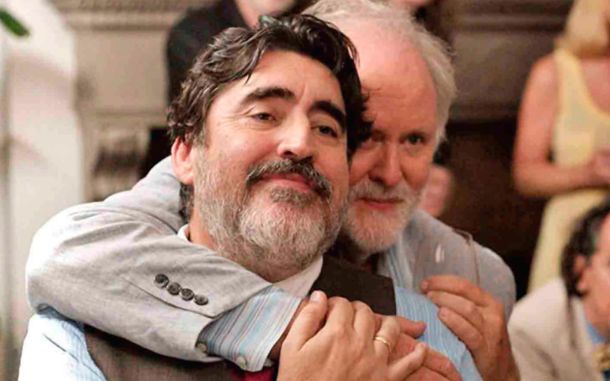

Playing a sexual nullity is a departure for Scott. He was the outrageously camp Lord Merlin in The Pursuit of Love (2017), the hot priest in Fleabag (2019), and the heartbreaking gay man in All of Us Strangers. He has also played “queer-coded” villains, such as Moriarty in BBC’s Sherlock (2010–17), and Max Denbigh (codenamed C) in Spectre (2015).

To the character of Ripley he brings an ambiguous charisma and a Machiavellian sapiosexuality – sexiness that comes from being very, very intelligent.

Scott’s one definite statement about Ripley is that “his sexuality or sensuality comes out of his relationship with things — art, clothes, props, music.” Certainly, his Ripley has a love/hate relationship with “things”. He desires Dickie’s pen, watch, ring and Picasso.

At the same time, inanimate objects prove to be obstacles as Ripley laboriously cleans up after his impulsive murders. There’s a boat he can’t burn or scupper, an elevator that seizes up when he is trying to carry a body downstairs. The ring almost proves his undoing. And as Slate culture columnist Laura Miller writes, “what is a corpse if not an inconvenient person transformed into an even more inconvenient thing?”

In his war with things, Scott’s Ripley reveals he is not talented. He makes mistakes. He is nearly caught several times. His botched coverups and his impatient sighs as he confronts yet another error, another chore, make the series “mordantly funny”.

These near-misses generate suspense and anxiety for Ripley, but he is too opaque, alien and other for empathy. Robert Elswit’s gorgeous black-and-white cinematography abets this, making the most of Scott’s obsidian eyes.

Scott’s performance raises a question that has divided critics: how blank is too blank?

Depending on whom you ask, his Ripley is either “mesmerizing” or “charmless”. Is Scott too successful at playing the incalculable other? Either way, this debate will certainly drive people to Ripley to see what all the fuss is about. ![]()

Written by Joy McEntee, Adjunct Senior Lecturer, University of Adelaide. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.