Face Value: The Unattainable Beauty Standards of Gay Culture

Humans are rather like magpies, easily distracted and drawn to pretty things. The magpie will see in the set of keys left on a park bench what we see in a TikTok dance: something small and dazzling to seize attention.

We are just as swift to peck that like button as the magpie is to swoop down and steal whatever metallic object takes its fancy.

Of course, this is nothing new.

You need only walk through a train station to be bombarded with a sea of pearly-toothed women advertising shampoo, or topless men with abs you could crack eggs on. There is, within western culture, the standard of body beauty which pre-eminently favours slender waists and glossy skin.

Yet the portrayal of gay men in visual media enforces stricter standards of body beauty than any other arena. In the narrow spaces where queer men are platformed, we are bedecked in ropes of pearls and blessed with triceps that burst out of our shirt sleeves.

The stereotypical portrayal of homosexual men as manicured, coiffured, and assembled in outfits that are always just so underlines the prevalence of body worship in gay culture. Open up Twitter and you will swiftly find at least eight selfies of muscular guys in bathroom mirrors, all of them rewarded with thousands of likes.

By and large, merit within gay culture is qualified by body beauty.

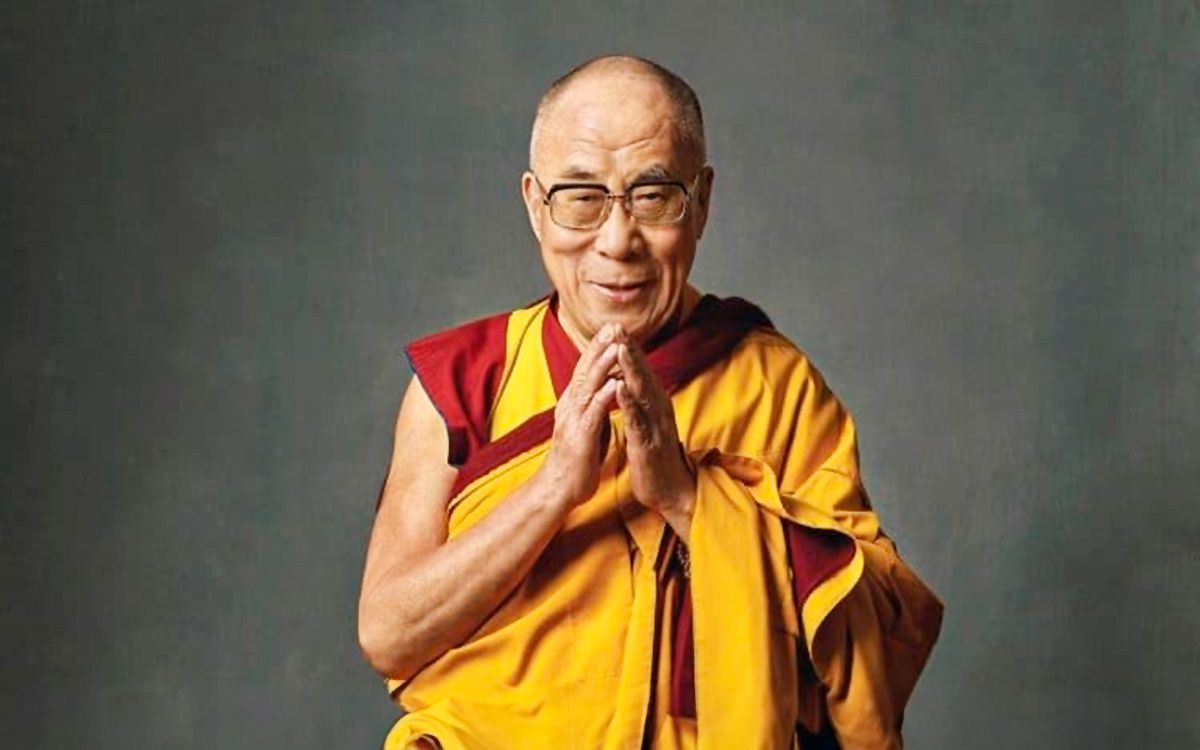

Speaking to the fickle nature of these beauty standards, Noah Losa, 28, proposes that rejecting this could represent a form of personal empowerment. A junior medical doctor invested in serving the wider queer community as an inclusive medical practitioner, Noah identifies as gender-fluid with he/they pronouns.

Photo: Noah Losa

“It is within our means to reject these beauty standards and instigate our own change, but it doesn’t mean it’s our fault if we haven’t.”

In the struggle for visibility commonly sought after by queer men, Noah argues that the LGBTQ+ community receives far greater overrepresentation of trauma than that of our heterosexual peers. “Let’s view these high beauty standards, then, through the lens of insecurity, trauma, and less-than-ideal sense of self.”

The struggle to belong “from the get go” is what upholds the need for acceptance. And this, for many queer people, is achieved externally. To be conventionally attractive serves as a survival mechanism for those rejected for their fundamental being.

“How many of us have felt that if we just make everything else perfect, and look flawless, perhaps society would be okay with that one little flaw of being queer? This is often at the expense of our integrity, though. We hide a part of ourselves, to be accepted. This is hard, nuanced, and layered work.

“I think the core thing is – if you have to choose between betraying yourself, or betraying someone else’s expectations – never betray yourself.”

This notion of palatability as a survival mechanism, of being agreeable within society, is one that follows the emergence of fitness trends throughout the AIDS crisis. Men who were physically fit and at least appeared to be healthy could disguise their degenerative illness. “These masculine elements of strength and muscles,” Noah says, “were thought to indicate the safety of a potential partner.”

More widely, there are considerations to be made that high beauty standards are present within all societal intersections. The remedy for this, Noah proposes, is the acknowledgement that it isn’t our fault.

“Attention is valuable within our current economic structure, and insecurity is a highly commodified trait. We’re all just trying to feel better, and it’s important to acknowledge the broader systemic issues beyond our own engagement in this challenge.”

They say this with the awareness that social media pits users against an algorithm which promotes insecurity for profit. “It isn't a conspiracy, it’s just capitalism.”

Photo: Noah Losa

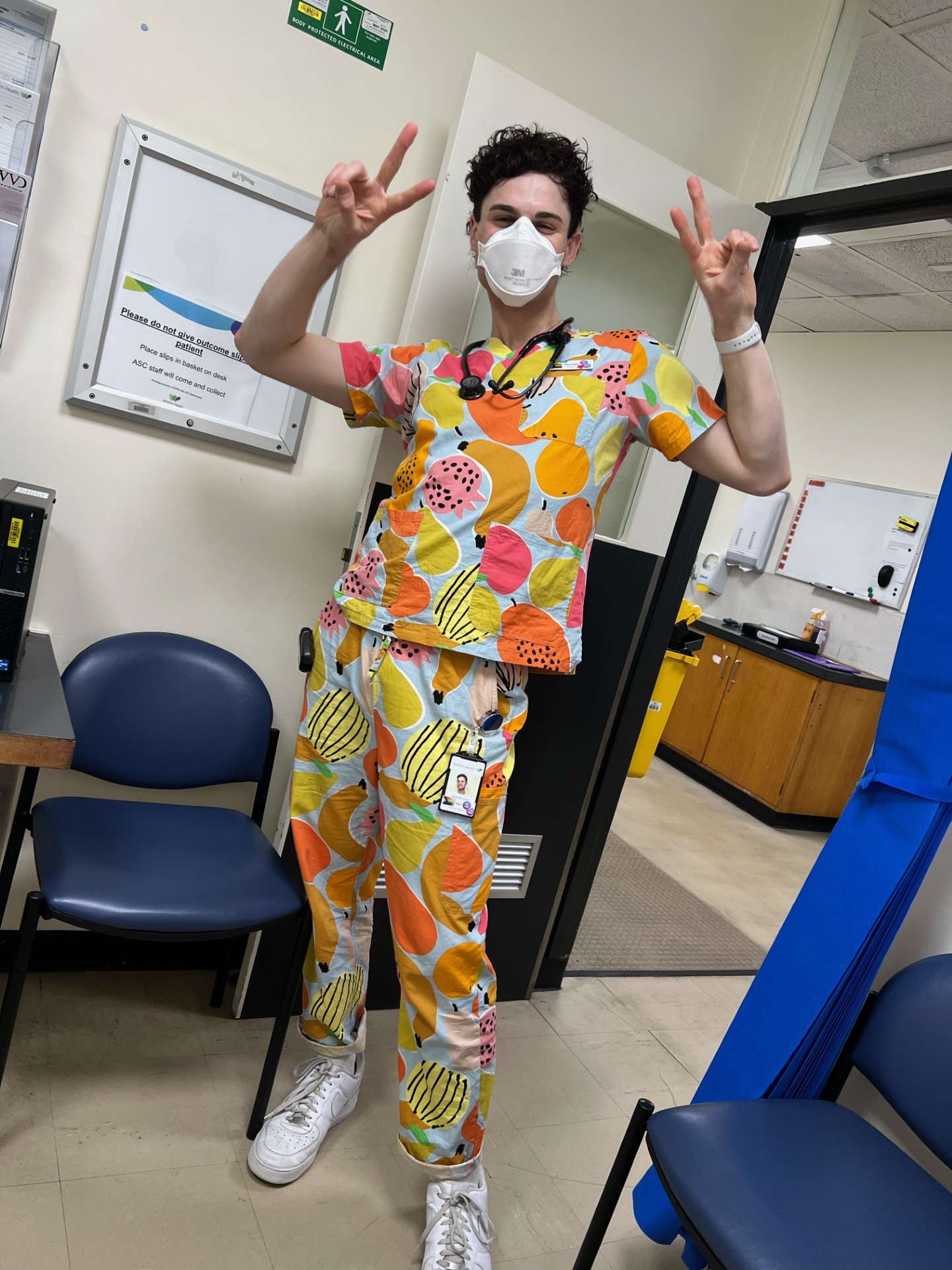

Echoing Noah’s views that beauty standards within gay culture are rooted in notions of hypermasculinity, Michael Di Iorio, 26, asserts that to be attractive “is to wash away all things that make you ‘queer’ or ‘feminine’ – even in queer spaces.”

With this comes the added pressure of being physically fit, “to constantly present the world with pictures of your white, toned and muscled body to receive approval from other white, toned and muscled men.”

A journalist and editor based in Sydney, where he freelances as a contributing writer for Pedestrian TV, Michael understands the rejection of body types outside of the Insta-friendly mould. His own fluctuating body type, from larger to thinner, affirmed as much in recent years.

Beyond this, “as a white male with queer friends who are people of colour,” there comes the realisation that skin tone plays as large a role within gay culture as the definition of one’s abs.

As Michael asserts, “I know I am treated differently in queer spaces based on the colour of my skin. Racism is undeniably entrenched in gay culture.”

Perhaps the largest shifts inside of gay culture for this generation has been the advent of social media. While visual media has long been an influential force behind contemporary trends, it is the predominant means by which information is communicated in the 2020s.

In Michael’s view, social media “has created an approach to content creation that values attractiveness over other attributes. It is a symptom of how social media operates. While there is seemingly no value to posting these pictures online, we have seen time and again how much our culture values being physically attractive.

Photo: Michael Di Iorio

“The idea that anybody can become a celebrity overwhelms today’s online culture, and it can be seen clearly in a gay man’s Instagram.”

The root of this behaviour stems from the search for approval that drives many queer men “raised in a society that deems us unworthy of love or adoration.” Substituting the encouragement and support that was absent in their developmental years, gay men instead find admiration and affection within the comments section of their social media posts.

An outsider who can receive inclusion and positive attention, so long as they look fit? “For most, this idea is overwhelmingly alluring,” Michael posits. “What’s not to love about positive attention? Whether this attention is based on genuine adoration, jealousy or insatiable lust doesn’t really matter.”

Operated and maintained by outsiders striving to receive acceptance, gay-centric social media inadvertently perpetuates another kind of exclusion.

Ironically, those who have themselves experienced rejection proceed to exercise it anew on social media platforms. And for what? Beauty remains as fickle as it has for time immemorial.

After all, what does the magpie do once it’s stolen that shiny pair of keys? It drops them in a bush the moment it spots the next glistening object of desire.

Liam Heitmann-Ryce-LeMercier, 27, is a writer and editor based in Melbourne. More of his writing, from further explorations of queer culture to the world of classical music, can be found in his portfolio.