Was famous bushranger Captain Moonlite gay?

Captain Moonlite, the Australian bushranger known for the Egerton bank robbery of 1869 and the Wantabadgery outrage of 1879, is commonly thought to have been gay or queer. In recent years, his love for gang member James Nesbitt has been celebrated in art, music and theatre.

Now the Heritage Council of New South Wales is considering adding the graves of Moonlite and Nesbitt to the State Heritage Register in recognition of their “publicly acknowledged same-sex relationship”.

The Heritage Council, however, has several issues to contend with. For one, the nature of the relationship between Moonlite and Nesbitt is not as sure and settled as has been assumed. For another, the headstone that now marks Moonlite’s grave obfuscates, rather than celebrates, his feelings for Nesbitt.

Meeting and memory

Andrew George Scott – the man behind the Moonlite moniker – met James Nesbitt in Pentridge Prison, Coburg, between 1875 and 1877. The two reunited on the outside in 1879, and Nesbitt followed Scott on his ill-fated trek into New South Wales where, with four other companions, they “stuck up” Wantabadgery Station.

In an ensuing confrontation with police, Nesbitt, August Wernicke (the youngest of Scott’s companions) and Constable Edward Mostyn Webb Bowen were all mortally wounded. Nesbitt and Wernicke were buried in unmarked graves in Gundagai Cemetery.

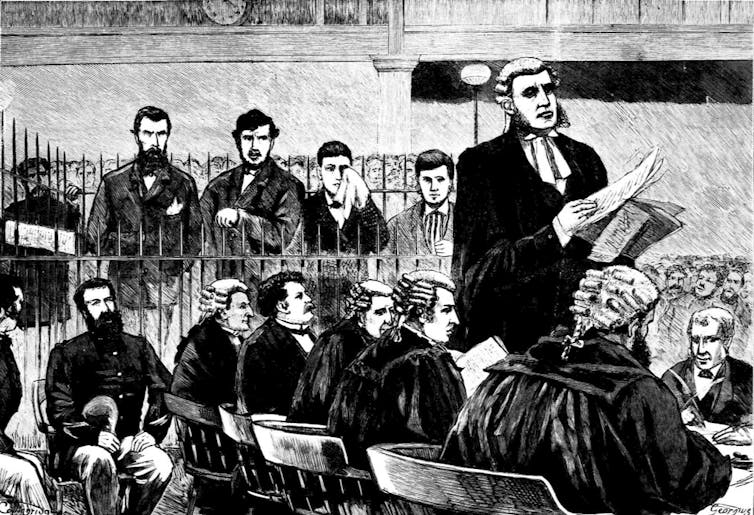

Scott and another of his companions, Thomas Rogan, were hanged for Bowen’s murder on January 20 1880. In the weeks leading up to this, as he awaited “the last dread sentence of the law” in a condemned cell in Darlinghurst Gaol, Sydney, Scott wrote numerous documents, including letters intended for friends, acquaintances, clergymen and Nesbitt’s parents. In these, he recorded he loved Nesbitt and wished to “fill the same grave” as him so they might be together forever.

Many of Scott’s letters were not sent and the wish they contained was not initially acted upon.

When Scott’s condemned-cell writings were rediscovered in the 1980s, they were swiftly assumed to reveal a romance. In the decades since, it has almost become a commonplace that Scott was homosexual and Nesbitt his lover.

Hidden histories

Determining the nature of a relationship from the past can be a complex matter. It requires, among other things, a sophisticated understanding of how emotions were expressed and how language was used in the relevant context. Phrases used to express romantic love today were not necessarily used in the same ways in the past.

Modern-day terms and concepts, from “homosexual” to “gay”, are also of limited use in understanding and describing historical people and their relationships. Before these terms and concepts were current, people understood themselves, their desires and their intimacies in other ways.

Unfamiliarity with the past, a yearning for queer forebears, and present-day views on sexuality have prevented us from seeing Scott and Nesbitt’s relationship as anything but romantic (in the everyday sense of the word) and sexual. And yet Scott’s language about Nesbitt conforms closely to the 19th-century concept of manly love – a bond between men which was “passing the love of women” precisely because it was free from any sexual element.

It is also significant that one of Scott’s preferred words to describe Nesbitt was simply “friend”: he was, Scott wrote to supporter John Alexander Dowie, “the truest best friend that man ever had”. It was in memory of a male friend that Tennyson penned his famous lines:

Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all.

Moonlite’s motivations

Two vital points must be recognised when approaching Scott’s writings about Nesbitt.

The first is all of Scott’s expressions of affection post-date Nesbitt’s death – a violent death, suffered at a young age, in consequence of decisions made by Scott. At the time of writing, Scott was suffering from intense trauma and grief – and as much as any emotion, Scott’s writings are evidence of grief.

The second relates to Scott’s intent. In the wake of his death, Scott was seeking to craft a legacy for Nesbitt. Nesbitt had died ignobly, while resisting the police, and was destined to be remembered as nothing but a scoundrel bushranger. Scott, however, wished him to be remembered otherwise: as honourable, truthful and brave. He even portrayed Nesbitt as Christ-like.

While it remains a possibility Scott and Nesbitt were lovers, as is commonly thought, Scott conveying as much in his condemned-cell writings would have undermined the image of Nesbitt (and himself) he was desperate to establish before his voice was silenced.

Moonlite’s grave

Scott’s remains were finally reinterred in Gundagai Cemetery in 1995, and marked by a headstone which reads:

ANDREW GEORGE SCOTT

CAPTAIN MOONLITE

BORN IRELAND 8-1-1845

DIED SYDNEY 20-1-1880“As to a monumental stone, a rough unhewn rock

would be most fit, one that skilled hands could

have made into something better. It will be like

those it marks as kindness and charity could have

shaped us to better ends.”

Andrew George Scott

Laid to final rest

near his friends James Nesbitt and Augustus

Wernicke who lie in unmarked graves close by.

Gundagai 13-1-1995.

This differs from what Scott specified in his condemned-cell writings: Nesbitt’s birth and death dates have been excluded, while Wernicke’s name has been added.

The quote is also an addition, albeit with a crucial omission: “As to the monumental stone for my friend and myself […]”. Without these italicised words, the visitor is led to infer that Scott intended his headstone to mark three people (himself, Nesbitt and Wernicke) and is distracted from Scott’s desire to occupy the grave of Nesbitt specifically.

Were the Heritage Council to proceed with its listing it would be both formalising a view of a historical relationship that is open to conjecture, and honouring a grave that deviates from the desires of the deceased.![]()

Matthew Grubits is a Historian at Charles Sturt University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.