- Home

- FUSE

- Features

- LGBTIQ History

- Trans life in Australia from the 1940s to 1970s

Trans life in Australia from the 1940s to 1970s

In December 1952, former American GI Christine Jorgensen made global news after undergoing gender affirmation surgery in Copenhagen. Australian newspapers showed great interest, with headlines like “Man Converted to Woman by Danish Doctors”, “Man Becomes Woman and ‘She Is Glad’”, and “‘Converted’ Girl Hopes to Marry”.

Readers are advised that this essay contains historical terms which are now generally considered outdated and offensive.

Jorgensen’s story even had an Australian angle: she intended to tour the country in late 1954 and appear in a series of fashion parades featuring Australian swimsuits, summer frocks and gowns. She also planned a cabaret-like performance at Sydney’s Palladium Theatre and in Melbourne. Local models protested, with one modelling agent saying,

A fashion parade featuring Miss Jorgensen would reek of the sort of sensationalism that’s popular in America, but isn’t suitable in Australia. For local girls to parade with him – I mean her – would lower our professional dignity.

The manager of the Palladium cancelled Jorgensen’s show and she called off her tour – though she did eventually visit Australia in 1961.

The media presented Jorgensen’s gender affirmation as a marvel of modern medicine and the embodiment of white, middle-class femininity. Jorgensen put a face and a name to emerging medical discourse about “transsexualism”, which American endocrinologist and sexologist Dr Harry Benjamin distinguished from “transvestism” in 1954:

It [transsexualism] denotes the intense and often obsessive desire to change the entire sexual status including the anatomical structure. While the male transvestite, enacts the role of a woman, the transsexualist wants to be one and function as one, wishing to assume as many of her characteristics as possible, physical, mental and sexual.

Jorgensen’s gender affirmation also presented Australians who were questioning their gender with new possibilities. Her endocrinologist received letters from 465 people around the world inquiring about the possibility of a “change of sex”. Thirteen such letters came from Australia: nine from assigned male at birth (AMAB) people and four from assigned female at birth (AFAB) people (there were also eight letters from Aotearoa New Zealand).

The changing language and possibilities as embodied in Christine Jorgensen are but one example of evolving understandings and lived experiences of trans people in the postwar period.

The rise of medical discourse about “transsexualism” and surgical options in Melbourne and Sydney offered new explanations and opportunities, particularly for those trans people who adhered to stereotypical ideas of white, middle-class respectability. The postwar era also saw the consolidation of camp cultures in the capital cities, bringing together a variety of sexually diverse and gender-diverse people.

World War II and its aftermath

Within World War II armed forces, there were surprising gender-crossing opportunities and trans possibilities. Drag performances were common as a form of entertainment, and were socially acceptable contexts in which AMAB people – be they gay or trans – could experiment with gender expression. There is also more concrete evidence of trans service members in accounts published after the war.

The Chameleon Society of Western Australia published a newsletter that told the tale of a member who served in the Australian Army and was seconded to a British regiment on the Rhine:

Well one day during a routine inspection, the RSM [regimental sergeant major] was going through the members kits and came across a whole heap of ladies apparel. The RSM grunted and said “You are Australian aren’t you?”, “Yes Sir” said our member. The RSM grunted and moved on leaving our member wondering what in the hell was going to happen. Well what did happen was rather remarkable. A few days later the RSM came across our member and pressed a card into his hand and said “I can recommend this club.” On it was a[n] address of a cross-dressing club in Hamburg.

During and after the war, a few new patterns emerged in media reports that shed light on trends around trans people. Coverage still primarily focused on cases with a salacious element, but one change was that more stories presented perspectives from the dressers themselves.

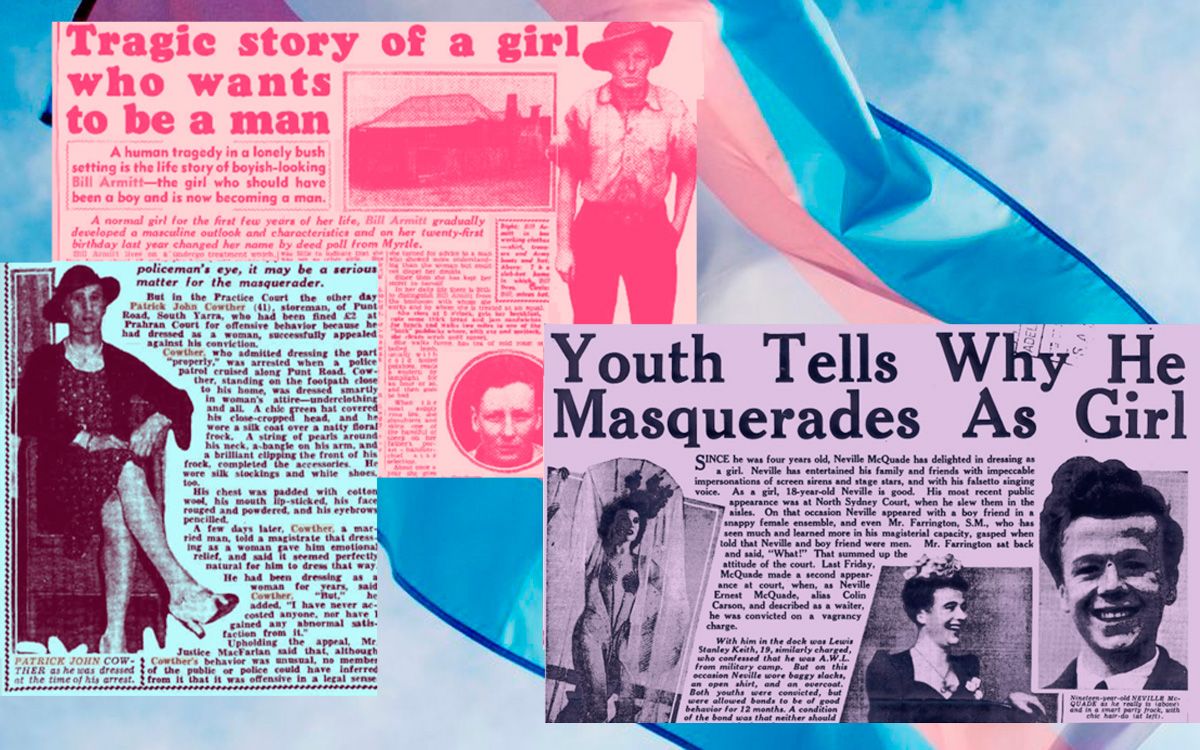

One such example was Patrick John Cowther, arrested in Melbourne in 1944 dressed in women’s clothes, a pearl necklace and a gold bangle and wearing lipstick, rouge, powder and eyeliner. Cowther admitted to wearing a pink nightdress to bed and, when their family was not around, dressing as a woman at home. They reportedly said to the police:

You gentlemen wouldn’t understand. It’s quite normal. Something inside me makes me want to do it. I’ve done it all my life. There are hundreds in England like me.

The tabloid Truth included more detailed coverage of this case, even publishing an image of Cowther dressed in women’s clothes. Their lawyer argued that there was nothing offensive about how Cowther dressed, and that Cowther dressed in women’s clothing as “an emotional relief … and to me it is perfectly natural”.

The magistrate disagreed: Cowther was convicted and fined £2.10. It is interesting that their solicitor was making arguments that aligned with contemporaneous understandings of “transvestism” yet did not use the word. The way Cowther expressed themself and invoked the existence of others was a sign of growing awareness about others “like them”.

As time went on, medical discourse gradually crept into press reports about dressing – particularly after the publicity surrounding Christine Jorgensen. For instance, police in Adelaide arrested John Martin Vernon Rounsevell while Rounsevell was dressed in women’s clothing, a wig and high heels and carrying a handbag.

Rounsevell admitted to dressing frequently as a woman and took police to a garage containing several boxes and a wardrobe full of women’s clothing. They said to police,

I cannot help myself. I am not telling lies. I have been to doctors and hope eventually to become a woman.

A psychiatrist testified that Rounsevell had been experiencing “transvestism” for at least 12 years and this compelled them to dress in women’s clothing. The judge accepted that Rounsevell suffered from a neurosis and released them on a £100 bond with the understanding that they would seek medical treatment.

Examples of AMAB defendants invoking medical defences, and magistrates accepting them, became more common in the 1960s. Coverage of AFAB people caught living as men tended to follow the prewar patterns of assuming it was for economic benefits, to seek adventure or to escape from an unhappy marriage. Yet there was the occasional AFAB person who invoked a desire to transition to being a man.

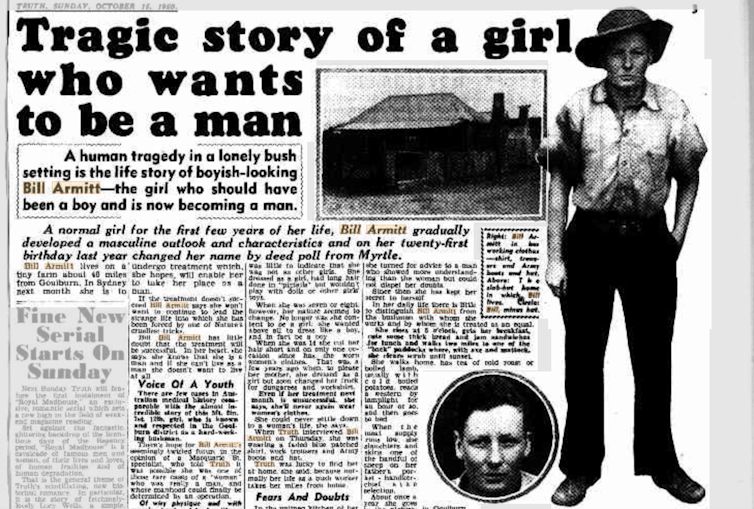

In October 1950 Truth reported about Bill Armitt, a 22-year-old AFAB person who said that over his lifetime he had gradually developed masculine characteristics.

Armitt had been wearing men’s clothes and had short hair since age 14; in 1949 he had changed his name and lived as a man with his father, working as a bushman. Armitt booked an appointment with a doctor to investigate if he were “one of those rare cases of a woman who is really a man” – the article implying that the specialist was referring to intersex variations.

A few weeks later, Truth reported that Armitt had undergone a gynaecological exam and the specialist had conclusively determined that he was a woman. Armitt did not accept this, remarking,

I don’t care what the doctors say. I know in my heart that I am a man and that I will always be a man. I don’t know what to do now. What can I do? […] If I can’t live as a man, I don’t want to live at all.

Armitt was referred to a psychologist but declined the consultation. He returned to Goulburn and his fate is not known.

The other emerging trend during this period was linking gender-crossing cases with the female impersonator scene. Theatre had always been a socially acceptable site for men to dress as women. By World War II, female impersonation represented an extension of this practice, combining dress, acting and singing and with impersonators appealing to audiences because of how convincing they were as women.

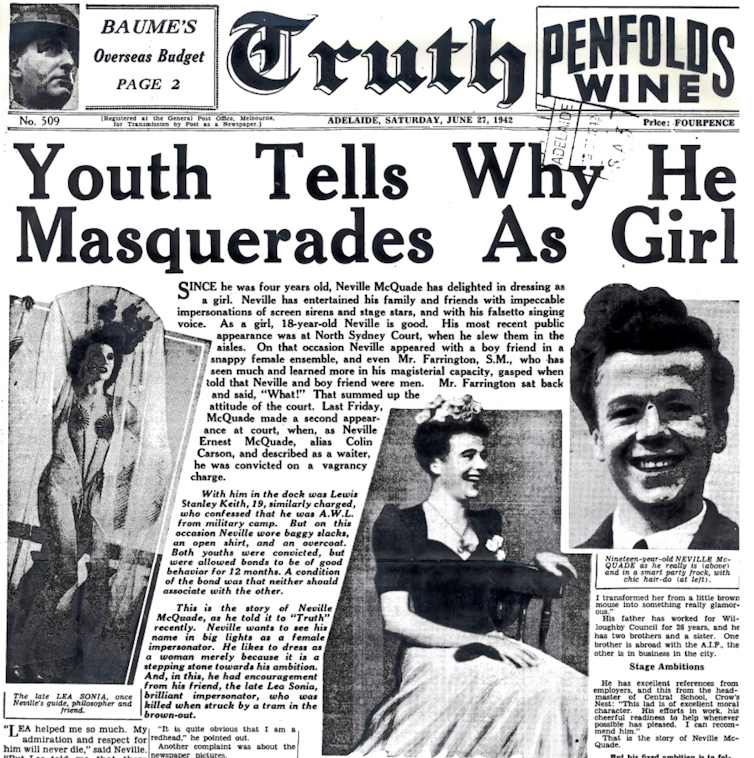

In the early 1940s Lea Sonia was perhaps Australia’s most famous female impersonator, described in one Truth article as “pos[ing] so convincingly as a woman fan dancer as to leave most of the audience still doubtful when the wig is removed at the end of the performances”.

Sonia died during a brownout in 1941 when she was hit by a tram while running for a taxi.

One person who cited the spectre of female impersonation was Neville McQuade, alias Colin Carson. McQuade appeared in the press on several occasions in the 1940s when arrested for vagrancy or offensive behaviour. In an interview with Truth, they expressed a desire to be famous like Lea Sonia, and regaled readers with descriptions of outfits and hair and desires to be a famous stage performer. McQuade was arrested a second time in 1943 for behaving in an offensive manner, being dressed as a woman and dancing with men.

Their third arrest was just after midnight on New Year’s Day 1944, for being dressed as a woman and dancing with a man on the streets of Newtown. On that occasion Dr Norman Haire testified for the defence and said McQuade was a “transvestist type” under his care. The magistrate fined McQuade £3 and released them on a 12-month good behaviour bond.

McQuade made one more appearance in the Australian media: in 1949 police arrested them, then living as Colin Carson, for having insufficient lawful means of support. Police also accused them of performing sex work with men, but McQuade vehemently denied this. They were quite open about continuing to dress in women’s attire and spoke about various social parties and balls that “were mostly frequented by perverts and their associates”.

McQuade’s appearances in the media across the 1940s collectively highlight the continuity and change when it came to gender crossing. Police were still arresting AMAB people dressed as women and laying charges such as offensive behaviour. There were also two emerging patterns that summarised the dominant trans subcultures and discourses until the 1980s: medicalisation and the camp scene. There was overlap between these two sites of trans visibility, but broadly speaking what separated them were the politics of respectability.

Medicalising transgender

In 1951, psychiatrist Dr Herbert Bower saw a patient at Melbourne’s Royal Park Mental Hospital who was AMAB but identified as a woman. Bower initially thought the patient was psychotic, but as he came to know them he realised the individual was well adjusted except for the gender identification. He had no clear diagnosis or treatment for them and subsequently continued to see patients with a different gender identity from their sex assigned at birth.

Bower’s early encounters with these individuals were around the same time that international medical discourse was concretising a pathology and language that built on the prewar sexology and new developments in surgery.

In 1949 Dr David Caldwell used the word “transsexual” to describe a person whose gender identification was different from their sex assigned at birth.

Dr Harry Benjamin’s aforementioned 1954 article Transsexualism and Transvestism as Psycho-Somatic and Somato-Psychic Syndromes explicitly distinguished “transvestism” from “transsexualism”. In 1966 Benjamin published The Transsexual Phenomenon, which became a global textbook for the medical treatment of “transvestites” and “transsexuals”.

Australians were conscious of these overseas developments because of the worldwide press they generated. Still, it was only Bower and a small number of psychiatrists who would treat local trans patients. Much of their work in the 1960s–70s centred on searching for a cause for people’s transness, as well as distinguishing between “transvestites”, “transsexuals” and effeminate homosexuals.

Richard Ball was one such psychiatrist associated with what are believed to be Melbourne’s first gender affirmation surgeries. The Victorian Health Department ran a Transsexualism Consultative Clinic from 1969. When Ball diagnosed people as “transsexuals”, he referred them to a surgeon who operated at Royal Melbourne Hospital, usually early on Saturday or Sunday mornings to keep away from conservative “prying eyes” in the general hospital system.

In 1975 Ball was appointed as professor of psychiatry at St Vincent’s Hospital, though the Transsexualism Consultative Clinic continued to run until 1987. Over its 18 years, according to later media reports, the clinic saw approximately 700 people and referred about 100 of them for gender affirmation surgery.

All cases had to go through a review panel before being accepted as a surgical candidate. The clinic’s approach represented an early example of a pattern that would echo across the country, as around the world.

First, psychiatrists made a distinction between “transvestites” and “true transsexuals”. To fit the criteria of a “true transsexual”, a person had to present as seeing themselves as the opposite gender trapped in the wrong body (this is known as “wrong body discourse”). What constituted the opposite gender reflected dominant social constructs framed around white, middle-class respectability.

The big distinction between “transvestites” and “transsexuals” was that the latter had to desire gender affirmation surgery and then to live indistinguishably, quietly, in their affirmed gender. Those individuals who did not meet the criteria would be denied treatment.

Sydney’s history of trans health care in the 1960s–70s has points of commonality with Melbourne’s, particularly around the role of psychiatrists and the need for a panel of specialists to approve surgery. Unverified newspaper reports and an oral history interview suggest Sydney was the site of Australia’s first gender affirmation surgery, in 1968. There were actually two gender clinics running in Sydney by the early 1970s, both directed by psychiatrists. One was at the Prince Alfred Hospital, but it closed in 1975 when the director accepted a position in Newcastle.

The most prominent personality behind trans psychiatry in 1970s Sydney was Neil McConaghy. McConaghy is a controversial figure in Australia’s history of sexuality and medicine because he was a practitioner of gay aversion therapy. When it came to trans people, though, he did not practise aversion therapy; indeed, his research and consultations at the Prince Henry Hospital were more in line with contemporaneous international ideas around “transvestism” and “transsexualism”.

McConaghy and psychiatrist Ron Barr also regularly deployed a “penile volume response test” – a mechanism that measured erectile responses to imagery – as part of their assessment process. They believed that “true transsexuals” were only attracted to men, which of course was a false supposition because sexuality is not the same as gender identity.

Justifying this belief, Barr wrote in 1976: “Patients who show a heterosexual pattern of response may live to regret the loss of the penis following surgery.”

Former patients do not speak fondly of the penile volume response test, which they found not only degrading but also absurd. “Sascha” (a pseudonym) recalls:

They would take us and they would connect our bits to a machine and then you’d be watching a film that would be flitting through the zoo and a baboon’s arse would flash up, and then you’d go a little bit further and there’d be this large, languid sort of Spanish-looking woman with huge, hairy tits, then she would be sort of lying there going like this and then you’d be flitting through the zoo again and there’d be a man’s penis and it was supposedly designed to measure your sexual responses when you came to any of these diversions.

Carlotta similarly writes in her autobiography:

they wired my penis and brain up and showed me photos of people in Kama Sutra positions, vaginas, penises and animals fucking, to see what my reactions would be. I was so angry and offended that I ripped off all the wires and stormed out.

Although Barr’s specific test did not continue after the 1970s, physical examinations including measuring of genitals certainly did – and this was not unique to Sydney.

When Sydney specialists approved trans people for surgery, the operations were performed at Prince of Wales Hospital. Those surgeries stopped in 1978. When questioned in a 1981 interview why, Barr gave the following explanation:

Well, several of us felt that, and the surgeon felt, he wasn’t entirely convinced it was helping […] I think being a transsexual is primarily an identity problem, not a sexual problem, because transsexuals are willing to take large doses of Oestrogens which greatly reduce/knock out sex drive and anybody who is primarily interested in sex would not take anything to know [sic] out their sex drive, they are more concerned with identity.

Transgender people have a different recollection about surgeries and why they ceased. Trans people sometimes spoke about surgeons who botched the procedures, with dire consequences. In an article in Cleo magazine sometime in the mid-1970s, performer Trixie Laumonte stated:

I wouldn’t have the operation in Sydney. I’ve seen too many botched up jobs here and it is a real tragedy […] Lots of surgeons are in sex change work for the money and I’ve seen some disgusting jobs. They can make a real mess of you and that’s when you get someone who is unhappy afterwards.

A few years earlier, the press reported about a stripper, Tiffany Jones, who died following complications from breast augmentation surgery in a private hospital.

“Sascha” very bluntly said in her oral history interview:

They [surgeons] mutilated so many people, and so many people just died from stuff that they did. They didn’t know what they were doing and it was awful, horrible.

She believes the Sydney surgeons were not properly trained to perform gender affirmation surgeries and that the trans women they operated on were like guinea pigs. She recollects one friend whom she describes as having been “butchered” by the surgeons. Eventually, that person died by suicide, which Sascha attributes in part to the surgery complications. Sascha believes the many complications from surgeries led Sydney surgeons to cease operating.

Although there are conflicting accounts as to why gender affirmation surgeries terminated in Sydney in 1978, by then viable alternatives had emerged in Melbourne and Adelaide.

Trans people navigating health care

Before the 1970s there were no trans organisations, no publicly advertised gender clinics and no internet to find doctors with knowledge or referral pathways. Some trans people desperately wrote to the media seeking advice. A letter to a Truth advice column published in 1966 read:

I am a male, and I want very badly to become a female. But I understand this operation is against the law in Australia. I have become very feminine in outlook and even my handwriting has changed. When I walk I roll my hips like a woman. I try not to walk like this, but I can’t help it. Can you help me get female hormones? – A.G. (South Australia)

The response was that the person might have a glandular problem and should seek referral to an endocrinologist.

Those trans people who approached psychiatrists had mixed results depending on the psychiatrist’s specialist knowledge and the resources available where the person lived.

The protocols that psychiatrists developed from the 1960s and 1970s were very rigid: they would assess if a person were a “true transsexual” and judge whether the person could, if given hormone treatment and gender affirmation surgery, blend indistinguishably with cis women. This was of course quite subjective, but it meant psychiatrists wielded significant power over trans people’s bodies and health care.

The psychiatrists expected trans women to wear dresses and apply stereotypical standards of white femininity (during this era it was almost always trans women, but in later periods psychiatrists would similarly expect trans men to dress and present like stereotypical men).

Psychiatrists by their own admission would deny treatment to those whom they considered not feminine enough or those who did not live sufficiently respectable lives, such as strippers and sex workers.

Those whom psychiatrists diagnosed as “true transsexuals” would be prescribed hormones by an endocrinologist and must live full time as women for two years – the “real-life test”, as it was called – before the psychiatrists would approve them for gender affirmation surgery. Trans people had to navigate these rigid boundaries and over time came to refer to psychiatrists as gatekeepers.

Trans people who did not meet psychiatrists’ approval were, to an extent, able to exercise agency and find other ways to secure hormones. One interview participant, Jazmin Theodora, remembers that as far back as the 1960s, “Someone started taking the hormones to get breasts, and then we all started taking them.”

She recalls a Dr Roger Gray who prescribed them without questions – exercising what is now known as the informed consent model. In Melbourne, Dr Harry Imber joined a St Kilda GP clinic in 1972 and by the late 1970s was known in trans circles for his willingness to prescribe hormones with informed consent – he even wrote about it in the Medical Journal of Australia in 1976.

Other trans people sourced hormones through the black market. In some instances this meant trans women who had legitimate prescriptions shared hormones with their friends.

In other circumstances it meant finding a chemist who was willing to sell them off-book, though always for higher than the normal retail price. When it came to gender affirmation surgeries, trans people had fewer options. Surgeries were limited to a small number of specialists in Melbourne and Sydney – not to mention the rigid gatekeeping expectations just to be eligible.

In extreme examples of desperation, people tried to perform gender affirmation surgery on themselves. A case from 1968 made the cover of Truth; the person had been taking feminising hormones and said they just could not live as a man. They were rushed to hospital, where they were reported as saying, “I did it myself with razor blades in the kitchen while my wife was in bed asleep.”

Trans people with some means could travel overseas for gender affirmation surgery. From the 1960s–70s the most common destinations were London (where those with British citizenship could have it done through the public system at Charing Cross Hospital), Hong Kong, Morocco and Egypt.

In 1962, PIX magazine ran a three-part firsthand account by a trans woman. In part one she described her lifetime struggle with gender. Part two detailed her numerous psychiatric assessments and meetings with surgeons in Melbourne who ultimately declined to perform the operation.

She managed to source feminising hormones from a chemist and tried other doctors in Sydney who also declined to refer her for surgery. Eventually, doctors in London approved her for gender affirmation surgery and even waived the costs.

The author explained that she was narrating her transition journey because:

It is the fervent hope that I will instil courage into those who, like me, have been condemned to twilight existence as neuters. Every scorn, every hostility that is heaped upon these poor people is an unnecessary scar. And I would beg of you who have cast the first stone in this direction to stay your hands.

This is an edited extract from Transgender Australia: A History Since 1910 by Noah Riseman (MUP). Noah Riseman, Professor in History, Australian Catholic University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.